The Bayeux Tapestry Is Unique in Romanesque Art Which of the Following Supports This Claim

The Bayeux Tapestry (, ; French: Tapisserie de Bayeux [tapisʁi də bajø] or La telle du conquest ; Latin: Tapete Baiocense) is an embroidered material nearly seventy metres (230 ft) long and 50 centimetres (20 in) tall[ane] that depicts the events leading upwardly to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, led by William, Knuckles of Normandy challenging Harold II, King of England, and culminating in the Battle of Hastings. It is thought to appointment to the 11th century, within a few years after the battle. It tells the story from the point of view of the conquering Normans but is now widely accustomed to have been made in England.

According to Sylvette Lemagnen, conservator of the tapestry, in her 2005 book La Tapisserie de Bayeux:

The Bayeux tapestry is one of the supreme achievements of the Norman Romanesque .... Its survival well-nigh intact over nine centuries is trivial curt of miraculous ... Its exceptional length, the harmony and freshness of its colours, its exquisite workmanship, and the genius of its guiding spirit combine to make it endlessly fascinating.[two]

The cloth consists of some seventy scenes, many with Latin tituli, embroidered on linen with coloured woollen yarns. It is likely that information technology was commissioned by Bishop Odo, William'due south maternal half-brother, and fabricated in England – non Bayeux – in the 1070s. In 1729, the hanging was rediscovered past scholars at a time when it was beingness displayed annually in Bayeux Cathedral. The tapestry is at present exhibited at the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Bayeux, Normandy, France ( 49°16′28″Due north 0°42′01″Westward / 49.2744°N 0.7003°W / 49.2744; -0.7003 ).

The designs on the Bayeux Tapestry are embroidered rather than in a tapestry weave, and then that information technology does not encounter narrower definitions of a tapestry.[3] Nevertheless, it has ever been referred to as a tapestry until recent years when the proper name "Bayeux Embroidery" has gained basis among certain art historians. Information technology can exist seen as a rare example of secular Romanesque art. Tapestries adorned both churches and wealthy houses in Medieval Western Europe, though at 0.5 by 68.38 metres (1.6 past 224.iii ft, and obviously incomplete) the Bayeux Tapestry is exceptionally large. Just the figures and decoration are embroidered, on a groundwork left plain, which shows the subject area very conspicuously and was necessary to cover large areas.

History [edit]

Origins [edit]

The primeval known written reference to the tapestry is a 1476 inventory of Bayeux Cathedral,[4] but its origins take been the discipline of much speculation and controversy.

French legend maintained the tapestry was deputed and created by Queen Matilda, William the Conquistador's wife, and her ladies-in-waiting. Indeed, in France, it is occasionally known every bit "La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde" (Tapestry of Queen Matilda). However, scholarly assay in the 20th century concluded it was probably deputed by William's half-brother, Bishop Odo,[v] who, after the Conquest, became Earl of Kent and, when William was absent-minded in Normandy, regent of England.

The reasons for the Odo commission theory include:

- three of the bishop'southward followers mentioned in the Domesday Book announced on the tapestry;

- it was found in Bayeux Cathedral, congenital by Odo; and

- it may have been commissioned at the same time equally the cathedral'south structure in the 1070s, possibly completed by 1077 in fourth dimension for brandish on the cathedral's dedication.

Assuming Odo commissioned the tapestry, information technology was probably designed and constructed in England past Anglo-Saxon artists (Odo's primary power base being by then in Kent); the Latin text contains hints of Anglo-Saxon; other embroideries originate from England at this time; and the vegetable dyes can be institute in fabric traditionally woven there.[vi] [vii] [viii] Howard B. Clarke has proposed that the designer of the tapestry was Scolland, the abbot of St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, considering of his previous position equally head of the scriptorium at Mont Saint-Michel (famed for its illumination), his travels to Trajan'south Column, and his connections to Wadard and Vital, ii individuals identified in the tapestry.[9] [10] The bodily physical work of stitching was near likely undertaken by female needleworkers. Anglo-Saxon needlework of the more detailed type known equally Opus Anglicanum was famous across Europe. It was perhaps commissioned for display in the hall of his palace and then bequeathed to the cathedral he built, following the pattern of the documented but lost hanging of the Anglo-Saxon warrior Byrhtnoth, bequeathed past his widow to Ely Abbey.[xi]

Alternative theories exist. Carola Hicks has suggested it could possibly have been deputed by Edith of Wessex, widow of Edward the Confessor and sister of Harold.[12] Wolfgang Grape has challenged the consensus that the embroidery is Anglo-Saxon, distinguishing between Anglo-Saxon and other Northern European techniques;[13] Medieval material authority Elizabeth Coatsworth[fourteen] contradicted this: "The endeavor to distinguish Anglo-Saxon from other Northern European embroideries before 1100 on the grounds of technique cannot be upheld on the basis of nowadays knowledge."[15] George Beech suggests the tapestry was executed at the Abbey of Saint-Florent de Saumur in the Loire Valley and says the detailed depiction of the Breton campaign argues for additional sources in France.[16] Andrew Bridgeford has suggested that the tapestry was actually of English language design and encoded with secret messages meant to undermine Norman rule.[17]

Recorded history [edit]

The first reference to the tapestry is from 1476 when it was listed in an inventory of the treasures of Bayeux Cathedral. It survived the sack of Bayeux past the Huguenots in 1562; and the side by side certain reference is from 1724.[eighteen] Antoine Lancelot sent a report to the Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres apropos a sketch he had received most a work concerning William the Conqueror. He had no idea where or what the original was, although he suggested information technology could have been a tapestry.[19] Despite further enquiries he discovered no more.

Montfaucon / Benoît drawing showing Male monarch Harold'southward death

The Benedictine scholar Bernard de Montfaucon made more successful investigations and found that the sketch was of a small-scale portion of a tapestry preserved at Bayeux Cathedral. In 1729 and 1730 he published drawings and a detailed description of the complete work in the first two volumes of his Les Monuments de la Monarchie française. The drawings were past Antoine Benoît, i of the ablest draughtsmen of that fourth dimension.[19]

The tapestry was kickoff briefly noted in English in 1746 by William Stukeley, in his Palaeographia Britannica.[twenty] The start detailed account in English was written past Smart Lethieullier, who was living in Paris in 1732–3, and was acquainted with Lancelot and de Montfaucon: it was not published, still, until 1767, every bit an appendix to Andrew Ducarel's Anglo-Norman Antiquities.[19] [21] [22]

During the French Revolution, in 1792, the tapestry was confiscated as public property to be used for covering military wagons.[18] It was rescued from a wagon past a local lawyer who stored it in his house until the troubles were over, whereupon he sent it to the urban center administrators for safekeeping.[19] Subsequently the Terror the Fine Arts Commission, fix to safeguard national treasures in 1803, required it to be removed to Paris for brandish at the Musée Napoléon.[19] When Napoleon abandoned his planned invasion of Britain the tapestry's propaganda value was lost and it was returned to Bayeux where the quango displayed information technology on a winding apparatus of two cylinders.[19] Despite scholars' concern that the tapestry was becoming damaged the quango refused to return it to the cathedral.[19]

Stothard / Basire engravings: scenes showing the Norman troops crossing the Channel and landing in Sussex

In 1816 the Guild of Antiquaries of London commissioned its historical draughtsman, Charles Stothard, to visit Bayeux to make an accurate hand-coloured facsimile of the tapestry. His drawings were subsequently engraved past James Basire jr. and published by the Club in 1819–23.[23] Stothard'south images are still of value equally a record of the tapestry every bit it was before 19th-century restoration.

By 1842 the tapestry was displayed in a special-purpose room in the Bibliothèque Publique. It required special storage in 1870 with the threatened invasion of Normandy in the Franco-Prussian State of war and over again in 1939–1944 by the Ahnenerbe during the High german occupation of France and the Normandy landings. On 27 June 1944 the Gestapo took the tapestry to the Louvre and on 18 August, three days before the Wehrmacht withdrew from Paris, Himmler sent a message (intercepted by Bletchley Park) ordering it to be taken to "a identify of safety", thought to be Berlin.[24] Information technology was only on 22 August that the SS attempted to accept possession of the tapestry, by which time the Louvre was once more in French hands.[24] After the liberation of Paris, on 25 August, the tapestry was again put on public display in the Louvre, and in 1945 it was returned to Bayeux,[19] where it is exhibited at the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux.

After reputation and history [edit]

The inventory listing of 1476 shows that the tapestry was being hung annually in Bayeux Cathedral for the week of the Feast of St John the Baptist; and this was yet the case in 1728, although by that time the purpose was merely to air the hanging, which was otherwise stored in a chest.[24] Clearly, the work was being well cared for. In the eighteenth century, the artistry was regarded equally crude or even fell—red and yellow multi-coloured horses upset some critics. Information technology was idea to be unfinished because the linen was non covered with embroidery.[24] All the same, its exhibition in the Louvre in 1797 caused a sensation, with Le Moniteur, which commonly dealt with foreign affairs, reporting on it on its first 2 pages.[24] It inspired a pop musical, La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde.[ citation needed ] It was because the tapestry was regarded as an artifact rather than a work of art that in 1804 information technology was returned to Bayeux, wherein 1823 1 commentator, A. L. Léchaudé d'Anisy, reported that "there is a sort of purity in its primitive forms, especially considering the land of the arts in the eleventh century".[24]

The tapestry was becoming a tourist attraction, with Robert Southey complaining of the need to queue to come across the work. In the 1843 Manus-book for Travellers in France by John Murray III, a visit was included on "Recommended Route 26 (Caen to Cherbourg via Bayeux)", and this guidebook led John Ruskin to become there; he would describe the tapestry as "the almost interesting affair in its way believable". Charles Dickens, however, was not impressed: "It is certainly the work of amateurs; very feeble amateurs at the outset and very heedless some of them besides."[24]

During the Second Earth War Heinrich Himmler coveted the piece of work, regarding it as "important for our glorious and cultured Germanic history".[24]

In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that the Bayeux Tapestry would exist loaned to Britain for public display. It had been expected to be exhibited at the British Museum in London in 2022, only a appointment has not yet been finalised. If information technology does cantankerous the Channel, it will be the start time that it has left France in 950 years, assuming as much evidence suggests that it was made in Canterbury.[25] [26]

Construction, design and technique [edit]

In common with other embroidered hangings of the early medieval catamenia, this piece is conventionally referred to as a "tapestry", although it is not a "true" tapestry in which the blueprint is woven into the material in tapestry weave; it is technically an embroidery, although information technology meets the traditional broader definition of "tapestry" equally: "A material fabric decorated with designs of ornamentation or pictorial subjects, painted, embroidered, or woven in colours, used for wall hangings, defunction, covers for seats, ..."[27]

The Bayeux tapestry is embroidered in crewel (wool yarn) on a tabby-woven linen ground 68.38 metres long and 0.five metres broad (224.three ft × 1.six ft) and using 2 methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures.[7] [8] Nine linen panels, between fourteen and iii metres in length, were sewn together subsequently each was embroidered and the joins were disguised with subsequent embroidery.[24] At the first join (outset of scene fourteen) the borders do not line upwards properly simply the technique was improved so that the later joins are practically invisible.[24] The pattern involved a broad key zone with narrow decorative borders meridian and bottom.[24] Past inspecting the woollen threads behind the linen it is apparent all these aspects were embroidered together at a session and the awkward placing of the tituli is not due to them being added subsequently.[24] Later generations have patched the hanging in numerous places and some of the embroidery (especially in the last scene) has been reworked.[24] The tapestry may well have maintained much of its original appearance—information technology now compares closely with a careful cartoon made in 1730.[24]

The end of the tapestry has been missing from time immemorial and the final titulus "Et fuga verterunt Angli" ("and the English left fleeing") is said to be "entirely spurious", added before long before 1814 at a time of anti-English sentiment.[xviii] Musset speculates the hanging was originally about one.five metres longer.[18] At the last section still remaining the embroidery has been almost completely restored but this seems to have been done with at least some regard to the original stitching.[eighteen] The stylised tree is quite unlike whatever other tree in the tapestry.[18] The start of the tapestry has also been restored but to a much lesser extent.[18]

Norton[note 1] has reviewed the various measurements of the length of the tapestry itself and of its nine individual linen panels. He has too attempted to estimate the size and architectural design of the 11th-century Bayeux Cathedral. He considers the tapestry would accept fitted well if it had been hung along the due south, west, and due north arcades of the nave and that the scenes it depicts tin be correlated with positions of the arcade bays in a way that would have been dramatically satisfying. He agrees with before speculation that a last console is missing—one that shows William's coronation and which he thinks was some three metres long. Norton concludes that the tapestry was definitely designed to exist hung in Bayeux Cathedral specifically; that it was designed to appeal to a Norman audition; and that information technology was probably designed for Bishop Odo so equally to be displayed at the dedication of the cathedral in 1077 in the presence of William, Matilda, their sons, and Odo.[29]

The chief yarn colours are terracotta or russet, blueish-greenish, deadening gold, olive green, and blue, with small amounts of nighttime blue or blackness and sage greenish. Later repairs are worked in low-cal yellow, orangish, and light greens.[7] Laid yarns are couched in identify with yarn of the same or contrasting colour.

The tapestry's central zone contains about of the action, which sometimes overflows into the borders either for dramatic effect or because depictions would otherwise exist very cramped (for example at Edward'southward death scene). Events take place in a long series of scenes which are more often than not separated by highly stylised trees. However, the trees are not placed consistently and the greatest scene shift, between Harold's audience with Edward after his return to England and Edward's burial scene, is non marked in any way at all.[xviii]

The tituli are normally in the fundamental zone merely occasionally use the peak border. The borders are otherwise mostly purely decorative and only sometimes does the decoration complement the action in the primal zone. The ornamentation consists of birds, beasts, fish and scenes from fables, agriculture, and hunting. There are frequent oblique bands separating the vignettes. There are nude figures, some of corpses from battle, others of a ribald nature.[18] A harrow, a newly invented implement, is depicted (scene 10) and this is the primeval known depiction. The picture of Halley's Comet, which appears in the upper edge (scene 32), is the starting time known picture of this comet.[18]

In 1724 a linen bankroll cloth was sewn on comparatively crudely and, in around the yr 1800, large ink numerals were written on the backing which broadly enumerate each scene and which are withal commonly used for reference.[xviii]

The unabridged Bayeux Tapestry. Individual images of each scene are at Bayeux Tapestry tituli. (Swipe left or right.)

Background [edit]

Background of the events depicted [edit]

In a series of pictures supported past a written commentary, the tapestry tells the story of the events of 1064–1066 culminating in the Battle of Hastings. The two main protagonists are Harold Godwinson, recently crowned King of England, leading the Anglo-Saxon English language, and William, Duke of Normandy, leading a mainly Norman army, sometimes called the companions of William the Conquistador.[18]

William was the illegitimate son of Robert the Magnificent, Knuckles of Normandy, and Herleva (or Arlette), a tanner'due south daughter. William became Duke of Normandy at the age of seven and was in control of Normandy past the age of 19. His half-brother was Bishop Odo of Bayeux.

King Edward the Confessor, king of England and almost lx years old at the time the tapestry starts its narration, had no children or any clear successor. Edward's mother, Emma of Normandy, was William's bang-up aunt. At that time succession to the English throne was not past primogeniture but was decided jointly by the king and by an associates of nobility, the Witenagemot.

Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex and the about powerful noble in England, was Edward's brother-in-law. The Norman chronicler William of Poitiers[thirty] reported that Edward had previously determined that William would succeed him on the throne, and Harold had sworn to honour this, and yet later that Harold had claimed Edward, on his deathbed, had made him heir over William. Nonetheless, other sources, such equally Eadmer dispute this claim.

Creative context [edit]

Tapestry fragments have been found in Scandinavia dating from the 9th century and it is thought that Norman and Anglo-Saxon embroidery developed from this sort of work. Examples are to be establish in the grave goods of the Oseberg send and the Överhogdal tapestries.[18]

A monastic text from Ely, the Liber Eliensis, mentions a woven narrative wall-hanging commemorating the deeds of Byrhtnoth, killed in 991. Wall-hangings were common by the tenth century with English language and Norman texts particularly commending the skill of Anglo-Saxon seamstresses. Mural paintings imitating draperies still be in French republic and Italy and there are 12th-century mentions of other wall-hangings in Normandy and French republic. A poem by Baldric of Dol might even describe the Bayeux Tapestry itself.[18] The Bayeux Tapestry was therefore not unique at the time it was created: rather it is remarkable for being the sole surviving example of medieval narrative needlework.[31]

Content [edit]

Events depicted [edit]

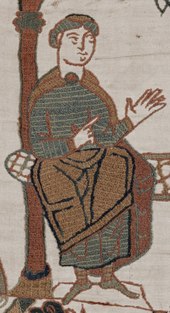

The tapestry begins with a panel of Edward the Confessor sending Harold to Normandy.(scene 1) Later Norman sources say that the mission was for Harold to pledge loyalty to William but the tapestry does not suggest any specific purpose.[24] Past mischance, Harold arrives at the wrong location in France and is taken prisoner by Guy, Count of Ponthieu.(scene 7) After exchanges of messages borne by mounted messengers, Harold is released to William who then invites Harold to accompany him on a campaign against Conan II, Duke of Brittany. On the way, just outside the monastery of Mont Saint-Michel, the army become mired in quicksand and Harold saves two Norman soldiers.(scene 17) William's army chases Conan from Dol de Bretagne to Rennes, and Conan finally surrenders at Dinan.(scene xx) William gives Harold arms and armour (possibly knighting him) and Harold takes an oath on saintly relics.(scene 23) Although the writing on the tapestry explicitly states an adjuration is taken there is no clue as to what is being promised.[24]

Harold leaves for domicile and meets again with the sometime king Edward, who appears to be remonstrating with him.(scene 25) Harold is in a somewhat submissive posture and seems to be in disgrace.[24] Still, possibly deliberately, the king's intentions are non made clear.[24] The scene then shifts by about one year to when Edward has get mortally sick and the tapestry strongly suggests that, on his deathbed, he bequeaths the crown to Harold.[annotation 2] [xviii] What is probably the coronation ceremony[note three] is attended by Stigand, whose position as Archbishop of Canterbury was controversial.[18] (scene 31) Stigand is performing a liturgical function, possibly not the crowning itself.[18] The tapestry labels the celebrant every bit "Stigant Archieps" (Stigand the archbishop) although by that fourth dimension he had been excommunicated by the papacy who considered his appointment unlawful.[24]

A star with a streaming tail, now known to be Halley's Comet, and so appears.[note 4] At this point, the lower border of the tapestry shows a fleet of ghost-like ships thus hinting at a future invasion.[24] (scene 33) The news of Harold'due south coronation is taken to Normandy, whereupon we are told that William is ordering a armada of ships to be built although it is Bishop Odo shown issuing the instructions.(scene 35) The invaders achieve England, and land unopposed. William orders his men to find nutrient, and a meal is cooked.(scene 43) A business firm is burnt by 2 soldiers, which may indicate some ravaging of the local countryside on the role of the invaders, and underneath, on a smaller scale than the arsonists, a adult female holds her male child's hand every bit she asks for humanity.(scene 47) News is brought to William.[note 5] The Normans build a motte and bailey at Hastings to defend their position. Messengers are sent betwixt the two armies, and William makes a speech to prepare his army for boxing.(scene 51)

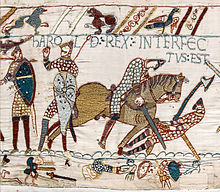

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 less than iii weeks subsequently the Boxing of Stamford Bridge but the tapestry does not provide this context. The English fight on foot behind a shield wall, whilst the Normans are on horses.[note 6] Two fallen knights are named as Leofwine and Gyrth, Harold'south brothers, but both armies are shown fighting bravely.[24] Bishop Odo brandishes his billy or mace and rallies the Norman troops in battle.(scene 54) [note 7] [24] To reassure his knights that he is still alive and well, William raises his helmet to show his face.[18] The battle becomes very bloody with troops being slaughtered and dismembered corpses littering the ground. King Harold is killed.(scene 57) This scene can be interpreted in dissimilar ways, every bit the name "Harold" appears above a number of knights, making it hard to identify which character is Harold, since one character appears with an pointer shot in his head under the name "Harold" while some other character is slain past a sword underneath the words "he is slain". The final remaining scene shows unarmoured English troops fleeing the battlefield. The final part of the tapestry is missing; however, it is thought that the story contained only one additional scene.[24]

People depicted [edit]

The post-obit is a list of known persons depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry:[32]

- Ælfgifu

- Archbishop Stigand

- Conan II, Knuckles of Brittany

- Edith of Wessex

- Edward the Confessor

- Eustace, Count of Boulogne

- Guy, Count of Ponthieu

- Hakon

- Harold, Earl of Wessex

- Leofwine Godwinson

- Odo, Bishop of Bayeux

- Robert the Staller

- Robert, Count of Mortain

- Scolland

- Turold

- Wadard

- William, Duke of Normandy

- Vital

Latin text [edit]

Tituli are included in many scenes to signal out names of people and places or to explain briefly the event being depicted.[xviii] The text is in Latin but at times the style of words and spelling shows an English language influence.[18] A dark blue wool, almost blackness, is more often than not used but towards the end of the tapestry other colours are used, sometimes for each word and other times for each letter of the alphabet.[18] The consummate text and English translation are displayed beside images of each scene at Bayeux Tapestry tituli.

Mysteries [edit]

Harold's death. Fable in a higher place: Harold rex interfectus est, "King Harold is killed"

Ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva

The depiction of events on the tapestry raises several mysteries:

- The identification of Harold II of England in the vignette depicting his expiry is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold is the figure struck in the middle with an arrow. The view that it is Harold is supported past the fact that the words Harold Rex (Rex Harold) appear right above the effigy's head. However, the pointer is a subsequently addition following a menses of repair,[18] every bit can be seen by comparison with Bernard de Montfaucon'due south engravings of the tapestry every bit it was in 1729, in which the pointer is absent (run into analogy above). However, needle holes in the linen do advise that something had originally been in the place of the arrow, though it may have been a lance rather than an pointer.[18] A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate, and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold'due south death (interfectus est, "he is slain"). This would appear to be more consistent with the labeling used elsewhere in the work. It was common medieval iconography that a perjurer was to dice with a weapon through the heart[ commendation needed ]. Therefore, the tapestry might exist said to emphasize William'south rightful claim to the throne by depicting Harold as an oath breaker. Whether he really died in this way remains a mystery and is much debated.[33]

- In that location is a console with what appears to be a clergyman touching or perchance hit a woman'south confront. No one knows the significance of this scene or the caption above information technology: ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva ("where [or in which] a certain cleric and Ælfgyva"), where Ælfgyva is the Latinised spelling of Ælfgifu, a popular Anglo-Saxon woman'due south name (literally "elf-gift").[24] The use of the character Æ shows familiarity with English language spelling.[24] There are two naked male figures in the edge beneath this figure; the i directly below the figure is in a pose mirroring that of the cleric, squatting and displaying his genitalia (a scene that was often censored in historical reproductions). However, like naked figures appear elsewhere in the lower border where there seems to be no connection at all with the master activity.[xviii] Harold had a younger sister named Ælfgifu (her name is spelt Alveva in the Domesday Volume of 1086) who was possibly promised to William by Harold or even betrothed to him, but she died c. 1066, prior to the invasion.[34] Ælfgifu was besides the name of the mother of Sweyn Knutsson and Harold Harefoot, past kings of Denmark and England respectively, via Cnut the Bang-up. It has been speculated that this scene, occurring after the coming together of Harold and William, is to remind the contemporary viewers of a scandal that occurred betwixt Ælfgifu of Northampton and Emma of Normandy, Cnut's wives, that somewhen led to the crowning of Edward the Confessor, child of Cnut and Emma.[17]

- At least two panels of the tapestry are missing, mayhap even another 6.4 m (vii.0 yd) in total. This missing area may accept depicted William's coronation equally King of England.[24]

Reliability [edit]

The Bayeux Tapestry was probably commissioned by the Firm of Normandy and essentially depicts a Norman viewpoint. However, Harold is shown as brave, and his soldiers are not belittled. Throughout, William is described equally dux ("duke"), whereas Harold, as well called dux upwards to his coronation, is afterward called male monarch ("king").[24] The fact that the narrative extensively covers Harold's activities in Normandy (in 1064) indicates that the intention was to show a strong relationship between that trek and the Norman Conquest starting ii years afterwards. It is for this reason that the tapestry is generally seen past modernistic scholars equally an apologia for the Norman Conquest.

The tapestry's narration seems to place stress on Harold's oath to William, although its rationale is not made articulate.[eighteen] Norman sources merits that the English succession was being pledged to William, but English sources requite varied accounts.[18] Today information technology is idea that the Norman sources are to be preferred.[35] Both the tapestry and Norman sources[36] name Stigand, the excommunicated archbishop of Canterbury, as the man who crowned Harold, possibly to ignominy Harold's kingship; one English source[37] suggests that he was crowned by Ealdred, archbishop of York, and favoured by the papacy, making Harold's position as legitimate male monarch more than secure. Contemporary scholarship has not decided the matter, although it is generally thought that Ealdred performed the coronation.[38] [39]

Although political propaganda or personal emphasis may take somewhat distorted the historical accurateness of the story, the Bayeux Tapestry constitutes a visual tape of medieval arms, dress, and other objects unlike any other artifact surviving from this menstruum. There is no try at continuity between scenes, either in individuals' appearance or clothing. The knights conduct shields, but testify no organisation of hereditary coats of arms—the beginnings of modern heraldic structure were in place, but would non become standard until the heart of the 12th century.[18] It has been noted that the warriors are depicted fighting with blank hands, while other sources indicate the general use of gloves in battle and hunt.

American historian Stephen D. White, in a study of the tapestry,[40] has "cautioned against reading it as an English or Norman story, showing how the beast fables visible in the borders may instead offer a commentary on the dangers of conflict and the futility of pursuing power".[41]

Replicas and continuations [edit]

A number of replicas of the Bayeux Tapestry take been created.

- Through the collaboration of William Morris with textile manufacturer Thomas Wardle, Wardle's married woman Elizabeth, who was an achieved seamstress, embarked on creating a reproduction in 1885.[24] She organised some 37 women in her Leek School of Art Embroidery to interact working from a full-scale h2o-color facsimile drawing provided by the South Kensington Museum. The full-size replica was finished in 1886 and is now exhibited in Reading Museum in Reading, Berkshire, England.[42] [43] The naked figure in the original tapestry (in the border below the Ælfgyva effigy) is depicted wearing a brief garment because the cartoon which was worked from was similarly bowdlerised.[24] The replica was digitised and made available online in 2020.[44]

- Ray Dugan of University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, completed a stitched replica in 1996.[45] Since its completion, it has been displayed in various museums and galleries in Canada and the The states.[46]

- In 2000, the Danish-based Bayeux Group, part of the Viking Grouping Lindholm Høje, began making an authentic replica of the Bayeux Tapestry, using the original sewing techniques.[47] The replica was completed in June 2014 and went on permanent exhibition at Børglum Abbey in May 2015.[48]

- Dr. Eastward. D. Wheeler, old judge and quondam dean at Oglethorpe University, deputed a hand-painted, full-size replica of the Bayeux Tapestry completed by Margaret ReVille and donated it to the University of Due west Georgia in Carrollton in 1994. In 2014, the replica was caused by the University of N Georgia in Dahlonega.[49]

Sections of the 1066 Medieval Mosaic re-creation in New Zealand

- An approximately one-half scale mosaic version of the Bayeux Tapestry was formerly on display at Geraldine, New Zealand.[fifty] Information technology was made up of ane.5 one thousand thousand vii mm2 pieces of spring steel—off-cuts from patterning disks of knitting machines—and was created past Michael Linton over a period of twenty years from 1979. The work was in 32 sections, and included a hypothetical reconstruction of the missing final department leading up to William the Conquistador's coronation at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, 1066.[51]

- Jason Welch, a woodcarver from North Creake, Norfolk, England, created a replica of the tapestry between 2011 and 2014 in carved and painted wooden relief on 25 five-foot planks. He undertook the projection to help cope with the grief of losing his 18-twelvemonth-old son.[52]

- Mia Hansson, from Skanör, Sweden, living in Wisbech, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, started a reproduction on thirteen July 2016. As of April 2022[update] she had completed 36 metres, saying that she expected to end in some 5 years. Hansson takes part of her replica out for talk and display events. In September 2020 she published Mia'due south Bayeux Tapestry Colouring Volume, with paw-drawn images from the tapestry.[53] [54]

Other modern artists take attempted to consummate the piece of work by creating panels depicting subsequent events upwardly to William's coronation, though the bodily content of the missing panels is unknown. In 1997, the embroidery artist Jan Messent completed a reconstruction showing William accepting the surrender of English nobles at Berkhamsted (Beorcham), Hertfordshire, and his coronation.[55] [56] [57] In early 2013, 416 residents of Alderney in the Aqueduct Islands finished a continuation including William's coronation and the edifice of the Tower of London.[58]

In popular culture [edit]

Street art in Bayeux referring to the Tapestry

Because it resembles a modern comic strip or picture storyboard, is widely recognised, and is so distinctive in its artistic style, the Bayeux Tapestry has oftentimes been used or reimagined in a diversity of different popular culture contexts. George Wingfield Digby wrote in 1957:

It was designed to tell a story to a largely illiterate public; it is like a strip cartoon, racy, emphatic, colourful, with a good deal of claret and thunder and some ribaldry.[59]

Information technology has been cited by Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics every bit an example of early sequential-narrative fine art;[lx] and Bryan Talbot, a British comic book artist, has chosen it "the first known British comic strip".[61]

It has inspired many mod political and other cartoons, including:

- John Hassall's satirical pastiche Ye Berlyn Tapestrie, published in 1915, which tells the story of the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914[62]

- Rea Irvin's cover for the New Yorker mag of 15 July 1944 mark D-Solar day[63]

- George Gale's pastiche chronicling the saga leading up to U.k.'s entry into the European Economic Community, published across six pages in The Times 's "Europa" supplement on i January 1973[64]

The tapestry has inspired modern embroideries, most notably and directly:

- The Overlord Embroidery (1974), commemorating Functioning Overlord and the Normandy landings of 1944, at present at Portsmouth

- The Prestonpans Tapestry (2010), which chronicles the events surrounding the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745

Other embroideries more loosely inspired past information technology include the Hastings Embroidery (1966), the New World Tapestry (1980–2000), the Quaker Tapestry (1981–89), the Great Tapestry of Scotland (2013), the Scottish Diaspora Tapestry (2014–15), Magna Carta (An Embroidery) (2014–15), and (in this case a woven tapestry with embroidered details) the Game of Thrones Tapestry (2017–nineteen).

A number of films take used sections of the tapestry in their opening credits or closing titles, including Disney's Bedknobs and Broomsticks, Anthony Mann'due south El Cid, Franco Zeffirelli'due south Hamlet, Frank Cassenti's La Chanson de Roland, Kevin Reynolds' Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and Richard Fleischer's The Vikings.[65]

The design and embroidery of the tapestry form ane of the narrative strands of Marta Morazzoni's 1988 novella The Invention of Truth.

The tapestry is referred to in Tony Kushner'due south play Angels in America. The apocryphal account of Queen Matilda'due south creation of the tapestry is used, perhaps in guild to demonstrate that Louis, one of the main characters, holds himself to mythological standards.[66]

In March 2022 the French specialist factual documentary Mysteries of the Bayeux Tapestry was circulate by BBC Four.[67] The programme explores both the history of the tapestry and the scientific and archaeological stories that lie within its embroidery. The original 90-infinitesimal documentary, written by Jonas Rosales, directed by Alexis de Favitski and produced by Antoine Bamas, was cut to 59 minutes for the BBC broadcast.[68] The documentary includes the work of scientists from the Laboratoire d'Archéologie Moléculaire et Structurale (LAMS) at the French National Center for Scientific Inquiry, using a hyperspectral camera, measuring 215 different colours, to analyse the verbal pigments used to produce the original colours for the dyed woollen threads, derived from madder, weld and indigo.[67]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Professor Christopher Norton is emeritus professor of History of Art at the University of York in the Eye for Medieval Studies.[28]

- ^ 5 Jan 1066.

- ^ 6 January 1066.

- ^ A comet was believed to be a bad omen at this time and Halley's comet would have showtime appeared in 1066 effectually 24 April, nearly four months after Harold'southward coronation.

- ^ Peradventure about Harold's victory in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, although the Tapestry does not specify this.

- ^ This reflected the armed forces reality.

- ^ Clerics were not supposed to shed blood, hence Odo has no sword. Rather than just praying for the Norman knights, nonetheless, which ought to accept been his role, Odo seems militarily active.

References [edit]

- ^ Caviness, Madeline H. (2001). Reframing Medieval Fine art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries. Medford, MA: Tufts University – via http://dca.lib.tufts.edu/caviness/. ; Koslin, Desirée (1990). "Turning Time in the Bayeux Embroidery". Material & Text. 13: 28–29. ; Bertrand, Simone (1966). La tapisserie de Bayeux. La Pierre-qui-Vire: Zodiaque. p. 23.

et combien pauvre alors ce nom de broderie nous apparaît-il!

- ^ Sylvette Lemagnen, Preface, p. 9; Musset, Lucien; Rex, Richard (translator) (1 November 2005) [1989]. La Tapisserie de Bayeux: œuvre d'art et certificate historique [The Bayeux Tapestry] (annotated edition) (Offset ed.). Woodbridge, United Kingdom: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 272. ISBN978-1-84383-163-1.

- ^ Saul, Nigel. "Bayeux Tapestry". A Companion to Medieval England. Stroud, UK: Tempus. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-7524-2969-8, but come across OED "Tapestry": "A material fabric decorated with designs of ornament or pictorial subjects, painted, embroidered, or woven in colours, used for wall hangings, defunction, covers for seats, ..." before mentioning "particularly" those woven in a tapestry weave.

- ^ Fowke, Frank Rede. The Bayeux Tapestry – A History and Description, London: G. Bell & Sons, 1913.

- ^ Sir Frank Stenton (ed) et al, The Bayeux Tapestry. A comprehensive survey London: Phaidon, 1957 revised 1965.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage nomination grade, in English and French. Word document. Published ix May 2006.

- ^ a b c Wilson, David One thousand.: The Bayeux Tapestry, Thames and Hudson, 1985, pp. 201–27

- ^ a b Coatsworth, Elizabeth (2005). "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery". In Netherton, Robin; Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (eds.). Medieval Clothing and Textiles. Vol. 1. Suffolk, Uk: Boydell & Brewer. pp. ane–27.

- ^ Clarke, Howard B. (2013). "The Identity of the Designer of the Bayeux Tapestry". Anglo-Norman Studies. 35.

- ^ "Designer of the Bayeux Tapestry identified". Medievalists.internet. Retrieved thirty October 2013.

- ^ Dodwell, C. R. (1982). Anglo-Saxon Fine art, a New Perspective. Manchester: Manchester Up. pp. 134–36. ISBN0-7190-0926-10.

- ^ "New Contender for The Bayeux Tapestry?", from the BBC, 22 May 2006. The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece, past Carola Hicks (2006). ISBN 0-7011-7463-3

- ^ See Grape, Wolfgang, The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph, Prestel Publishing, 3791313657

- ^ "Oxford Bibliographies Online – Author (Contributor: Elizabeth Coatsworth)". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Coatsworth, "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", p. 26.

- ^ Beech, George: Was the Bayeux Tapestry Made in France?: The Instance for St. Florent of Saumur. (The New Middle Ages), New York, Palgrave Macmillan 1995; reviewed in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume ii, Woodbridge, Suffolk, Great britain, and Rochester, New York, the Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN 1-84383-203-8

- ^ a b Bridgeford, Andrew, 1066: The Subconscious History in the Bayeux Tapestry, Walker & Visitor, 2005. ISBN 1-84115-040-ane

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j thousand l m n o p q r s t u 5 w x y z aa Musset, Lucien (2005). The Bayeux Tapestry. Boydell Press. ISBNi-84383-163-5.

- ^ a b c d east f g h Bertrand, Simone (1965) [1957]. "The History of the Tapestry". In Stenton, Frank (ed.). The Bayeux Tapestry (revised ed.). London: Phaidon Press. pp. 88–97.

- ^ Dark-brown 1988, p. 47.

- ^ Brown 1988, p. 48.

- ^ Hicks 2006, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Dark-brown 1988, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 one thousand due north o p q r s t u v due west ten y z aa ab ac Hicks, Carola (2006). The Bayeux Tapestry. The Life Story of a Masterpiece. Chatto and Windus. ISBN0-7011-7463-iii.

- ^ For case, illustrations in the Bayeux Tapestry can be shown to have been copied from the One-time English Hexateuch, formerly held in Canterbury, and Canterbury was Bishop Odo's English language power-base.

- ^ "Bayeux Tapestry to be displayed in Britain". The Times. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ OED, "Tapestry", which goes on to mention "peculiarly" those woven in a tapestry weave.

- ^ "Christopher Norton - History of Fine art, The University of York". www.york.air conditioning.u.k..

- ^ Norton, Christopher (23 Oct 2019). "Viewing the Bayeux Tapestry, Now and Then". Periodical of the British Archaeological Association. 172 (1): 52–89. doi:ten.1080/00681288.2019.1642012.

- ^ William of Poitiers: Gesta Willelmi ducis Normannorum et regis Anglorum, c.1071.

- ^ Wingfield Digby, George (1965). "Technique and Production". In Stenton, Frank (ed.). The Bayeux Tapestry (2d ed.). Phaidon Press. pp. 37–55 (37, 45–48).

- ^ "People identified on the tapestry". bayeux-tapestry.org.uk . Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Foys, Martin (2009). Pulling the Arrow Out: The Legend of Harold's Death and the Bayeux Tapestry. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 158–75. ISBN978-1-84383-470-0.

- ^ Mason, Emma (2004). The House of Godwine: the history of a dynasty. London: Hambledon and London. ISBN1852853891.

- ^ Bates, David (2004). "William I". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Printing. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29448. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ William of Poitiers: Gesta Willelmi ducis Normannorum et regis Anglorum, c.1071. Orderic Vitalis Historia Ecclesiastica, c.1123-1131.

- ^ Florence of Worcester / John of Worcester Chronicon ex Chronicis completed c.1140.

- ^ Gibbs-Smith, Charles (1965). "Notes on the Plates". In Frank Stenton (ed.). The Bayeux Tapestry. Phaedon Printing.

- ^ Cowdrey, H. E. J. (2004). "Stigand (d. 1072)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:ten.1093/ref:odnb/26523. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ "ACLS American Quango of Learned Societies - www.acls.org - Results". www.acls.org. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Prufrock: The Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry, When Israeli Prisoners Translated 'The Hobbit,' and the French 'Anti-Keynes'". The Weekly Standard. 25 Jan 2018.

- ^ "United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland'south Bayeux Tapestry at the Museum of Reading". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Bayeux Gallery". Reading Museum. 3 April 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Britain's Bayeux Tapestry". Reading Museum. 22 January 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Ray Dugan'southward Bayeux Tapestry". Dugansbayeuxtapestry.com. Retrieved 30 Apr 2012.

- ^ "Bayeux Tapestry, topic of seminar". Newsrelease.uwaterloo.ca. xv March 2001. Retrieved xxx April 2012.

- ^ "Vikingerne kommer!" [The Vikings Are Coming!] (in Danish). Kristeligt Dagblad. 30 November 2005.

- ^ "Nu hænger Bayeux-tapetet i en hestestald i Vendsyssel" [The "Bayeux tapestry" displayed in a horse stable in North Jutland]. Politiken. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "History center to display Bayeux Tapestry replica". Academy of North Georgia . Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Linton, Michael. "The Medieval Mosaic The Recreation of the Bayeux Tapestry, as a 34 metre Medieval Mosaic Masterpiece". Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 17 Baronial 2011.

- ^ "A Medieval Mosaic (Medieval Mosaic)". 1066. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Lazzari, Adam (14 January 2014). "Photo gallery: Norfolk man creates a 135ft wooden version of the Bayeux Tapestry to aid cope with his son's death". Dereham Times . Retrieved fifteen June 2020.

- ^ Hansson, Mia (2020). Mia's Bayeux Tapestry Colouring Book. March: Eyrie Printing. ISBN978-1-913149-eleven-6.

- ^ Hansson, Mia. "Mia'due south Bayeux Tapestry Story". Facebook . Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Berkhamsted Castle". Berkhamsted Local History Society . Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Invasion of England, Submission to William" (PDF). Castle Panels. Berkhamsted Castle. Archived from the original (PDF) on viii July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2013. (discussed in "Castle Panels". 2014. Archived from the original on 19 Feb 2014. Retrieved 11 Feb 2014. )

- ^ Messant, Jan (1999). Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers' Story. Thirsk: Madeira Threads. p. 112. ISBN978-0-9516348-v-ane.

- ^ "Bayeux Tapestry ending made in Alderney". BBC News. ix February 2013.

- ^ Wingfield Digby, "Technique and Production", p. 37.

- ^ McCloud 1993. Understanding Comics pp. 11–xiv

- ^ The History of the British Comic, Bryan Talbot, The Guardian Guide, 8 September 2007, p. five.

- ^ Hassall, John (2014) [1915]. Ye Berlyn Tapestrie. Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN978-one-85124-416-4.

- ^ "The New Yorker". Condé Nast. 15 July 1944. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Steven, Alasdair (24 September 2003). "George Gale: Obituary". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on three November 2014. Retrieved iii November 2014.

- ^ "Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: The Flip Side of History in Opening and Cease Championship Sequences" (PDF). Richard Burt, University of Florida. eighteen August 2007. Archived from the original on eight September 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ SparkNotes Editors. "SparkNote on Angels in America". SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. Retrieved xxx October 2014.

Louis's trouble is exacerbated past his tendency towards brainchild and his unreasonably high standards for himself. In Scene Three, he tells Emily about La Reine Mathilde, who supposedly created the Bayeux Tapestry. Louis describes La Reine's unceasing devotion to William the Conquistador and laments his own comparative lack of devotion. Just every bit critic Allen J. Frantzen has pointed out, this popular story about Mathilde and the tapestry is wrong—it was actually created in England decades afterwards the conquest. Louis, then, is property himself to a mythological standard of loyalty, and he curses himself based on a positively unreal instance. This is part of a larger pattern of excessive guilt and harshness toward himself, which, paradoxically, prevents him from judging his ain weaknesses accurately and trying to right them. Because no one could possibly live upward to Mathilde'south instance, Louis initially justifies his moral failure. Afterwards, in Perestroika, he will make it at a more genuine remorse and an honest agreement of what he has done.

- ^ a b "BBC Four - Mysteries of the Bayeux Tapestry". BBC.

- ^ Elmes, John. "BBC4 to reversion Bayeux Tapestry doc". Broadcast.

Further reading [edit]

- Backhouse, Janet; Turner, D. H.; Webster, Leslie, eds. (1984). The Aureate Age of Anglo-Saxon Fine art, 966–1066. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN0-7141-0532-5.

- Bernstein, David J. (1986). "The Mystery of Bayeux Tapestry" Weidenfeld and Nicolson ISBN 0-297-78928-vii

- Bloch, Howard (2006). A Needle in the Correct Hand of God: The Norman Conquest of 1066 and the Making and Significant of the Bayeux Tapestry. Random House ISBN 978-i-4000-6549-3

- Bridgeford, Andrew (2005). 1066 : the subconscious history in the Bayeux Tapestry Walker & Company ISBN 978-0-8027-7742-3

- Brownish, Shirley Ann (1988). The Bayeux Tapestry: History and Bibliography . Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN978-0-85115-509-viii.

- Burt, Richard (2007). "Loose Threads: Weaving Around Women in the Bayeux Tapestry and Cinema", in Medieval Film, ed. Anke Bernau and Bettina Bildhauer Manchester University Press

- Burt, Richard (Summer 2007). "Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: the Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences," special consequence of Exemplaria on "Movie Medievalism," nineteen.2., 327–50, co-edited by Richard Burt.

- Burt, Richard (2009). "Border Skirmishes: Weaving Around the Bayeux Tapestry and Movie house in Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves and El Cid." In Medieval Film. Ed. Anke Bernau and Bettina Bildhauer (Manchester: Manchester Upwardly), pp. 158–18.

- Burt, Richard (2008). Medieval and Early Modern Motion picture and Media (New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan), xiv; 279 pp. Paperback edition, 2010.

- Campbell, G. W (1984). "Aelfgyva : The Mysterious Lady of the Bayeux Tapestry" Annales de Normandie, V. 34, northward. 2, pp. 127–45.

- Foys, Martin K. (2003). Bayeux Tapestry Digital Edition. Private licence ed; CD-ROM. On-line version, 2013 [ permanent dead link ]

- Foys, Martin M., Overbey, Karen Eileen Overbey and Terkla, Dan (eds.) (2009) The Bayeux Tapestry: New Interpretations, Boydell and Brewer ISBN 978-1783271245.

- Gibbs-Smith, C. H. (1973). The Bayeux Tapestry London; New York, Phaidon; Praeger

- Hicks, Carola (2006). The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN978-0-7011-7463-7.

- Jones, Chas (2005). "The Yorkshire Preface to the Bayeux Tapestry" The Events of September 1066 – Depicted In a Customs Tapestry, Writers Impress Shop, start edition. ISBN 978-1-904623-37-3

- Pastan, Elizabeth Carson, and Stephen White, with Kate Gilbert (2014). The Bayeux Tapestry and its Contexts: A Reassessment. Boydell Press ISBN 978-1-84383-941-5.

- Rud, Mogens (1992). "The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066", Christian Eilers Publishers, Copenhagen; contains full colour photographs and explanatory text

- Werckmeister, Otto Karl (1976). "The Political Ideology of the Bayeux Tapestry." Studi Medievali, 3rd Series 17, no. 2: 535–95.

- Wilson, David McKenzie (ed.) (2004). The Bayeux Tapestry: the Complete Tapestry in Color, Rev. ed. New York: Thames & Hudson ISBN 978-0-500-25122-5, 0-394-54793-iv (1985 ed.). LC NK3049.

- Wissolik, Richard David (1982). "Duke William's Messengers: An Insoluble, Reverse-Guild Scene of the Bayeux Tapestry." Medium Ævum. L, 102–07.

- Wissolik, Richard David (March 1979). "The Monk Eadmer equally Historian of the Norman Succession: Korner and Freeman Examined." American Benedictine Review, pp. 32–42.

- Wissolik, Richard David. "The Saxon Argument: Code in the Bayeux Tapestry." Annuale Mediævale. 19 (September 1979), 69–97.

- Wissolik, Richard David (1989). The Bayeux Tapestry. A Critical Annotated Bibliography with Cantankerous References and Summary Outlines of Scholarship, 1729–1988, Greensburg: Eadmer Printing.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Bayeux Tapestry at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bayeux Tapestry at Wikimedia Commons - Bayeux Tapestry – Bayeux Museum

- Digital exploration of the tapestry

- Loftier quality panoramic image of Bayeux Tapestry (Bibliotheca Augustana)

- A Guide to the Bayeux Tapestry – Latin-English translation

- The Bayeux Tapestry – drove of videos, manufactures and bibliography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. three (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 555–556. With 16 images

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayeux_Tapestry

Postar um comentário for "The Bayeux Tapestry Is Unique in Romanesque Art Which of the Following Supports This Claim"